My mother was an artist. Both my brothers attribute at least some of their artistic talent to her, and I know my desire to write and to become a photographer was often encouraged by her - if not in words, in her actions. Yet I experienced a very different woman as I grew up than my brothers and sister knew. By the time I was in early adolescence, the artist had taken a serious backseat to the alcoholic, and though I saw glimmers of her talent with a pen and pencil, it was only the briefest of glimpses. In my own quest to find some art form or way of expressing myself, I grew up with a very potent unspoken message - that it is impossible to find one's path through art. I carried that belief with me up to the day I heard Paul Caponigro speak to the 1979 Ansel Adams Workshop attendees, other instructors and even Ansel himself.

George and I arrived early and put our jackets on chairs front and center, then browsed the matted fine-art portfolio prints Caponigro had put out on display, covering two eight-foot tables entirely. All black-and-white, they were soft and delicate images of his travels, images I have still, enclosed in the pages of his coffee-table book Megaliths. I stopped at the table that held his books, and bought the one I felt I could afford at the time, Landscape, intending on getting him to sign it at the end of the lecture. I took it with me as I went out the front entrance to have a cigarette 15 minutes before he was to speak. The entryway I found myself in had low stone walls on either side of the sidewalk, and as I sat on one side and lit up, I noticed I was directly opposite Caponigro and another man, presumably either a student or assistant to one of the other instructors. They were engaged in a quiet but obviously intense conversation, speaking in low tones. For a few minutes I kept what I thought was a clandestine eye on them while browsing the book I had just purchased. Then they both seemed to relax and disengage from their conversation. The other person said something to a student walking by, and I looked up just as Caponigro turned and looked directly at me. We stared at each other for what seemed an abnormally long time.

You know those rare moments in time when you and another person connect on a level that surprises you? This was that, times ten...or maybe twenty-five. I don't know how to quantify it, but I know that at that moment I was a bit exposed emotionally - raw even, from the other events of that day, and when we locked gazes I felt like he was looking deep into me. It was unnerving, but I didn't - couldn't - look away. It felt like a long time before his companion said something to him and he blinked (is it in my imagination of the moment, or did it really happen that he nodded?) and looked away. I realized at that point that I had been holding my breath, and blinked myself, then exhaled and stubbed out my cigarette and sat while he stood. Four other people joined him and together they walked into the lecture hall. All I could think was, "What was that?"

I staggered to my feet and shook my head, then followed the parade of people headed in. I took my seat next to George, and I don't remember what happened next. I do know Caponigro took the podium on stage and began speaking about his journey as a photographer, how he saw the art as an avenue to his own spirituality, how his training as a classical pianist had contributed to his photography - something he and Ansel had in common - and how if we wanted a pathway to self-discovery and a way of seeing that was uniquely our own - a seeing into ourselves and what this life could hold for us - then photography just might be the answer.

Remember the first paragraph of this post? The one sitting up there pregnant with all the lost possibility of a life lived to its fullest? My mother's life? An artist who never got to get there, to the point Caponigro was describing, the religion surrounding the desire to create that had the potential to save her from the life she ultimately ended up living? That paragraph can't begin to hold all the pain and sadness that suddenly washed over me with each new statement that Paul Caponigro made on stage that evening. A half-an-hour in, I was far more than exposed. I was turned inside out. Without a word to George, I stood up and walked out. I went to the restroom, and for ten minutes I wept. I wept for the child I used to be. But more, I wept for my mother, and all the dreams she left in all those empty bottles. And somewhere in those ten long minutes alone in a cold public restroom surrounded by the mountains of Yosemite, I grasped the thread of what has become my life. I left the belief that you can never live your art on that bathroom floor, wrapped up in tissue, and as sad as I was for my mother, I was equally as determined to never let that happen to me.

I composed myself eventually (so to speak), and walked back into the hall, but I didn't go back to my seat. I was aware enough of the epiphany that was being born inside me to know I was going to buy one of Paul Caponigro's prints that evening. I just didn't know which one. And all his prints were just inside the door on those tables, with no one else around. Everyone was listening to him as he continued speaking and I listened also as I walked around the tables, narrowing down my choice. It didn't take as long as you might think. Before he was done, I had it down to two prints:

George and I arrived early and put our jackets on chairs front and center, then browsed the matted fine-art portfolio prints Caponigro had put out on display, covering two eight-foot tables entirely. All black-and-white, they were soft and delicate images of his travels, images I have still, enclosed in the pages of his coffee-table book Megaliths. I stopped at the table that held his books, and bought the one I felt I could afford at the time, Landscape, intending on getting him to sign it at the end of the lecture. I took it with me as I went out the front entrance to have a cigarette 15 minutes before he was to speak. The entryway I found myself in had low stone walls on either side of the sidewalk, and as I sat on one side and lit up, I noticed I was directly opposite Caponigro and another man, presumably either a student or assistant to one of the other instructors. They were engaged in a quiet but obviously intense conversation, speaking in low tones. For a few minutes I kept what I thought was a clandestine eye on them while browsing the book I had just purchased. Then they both seemed to relax and disengage from their conversation. The other person said something to a student walking by, and I looked up just as Caponigro turned and looked directly at me. We stared at each other for what seemed an abnormally long time.

You know those rare moments in time when you and another person connect on a level that surprises you? This was that, times ten...or maybe twenty-five. I don't know how to quantify it, but I know that at that moment I was a bit exposed emotionally - raw even, from the other events of that day, and when we locked gazes I felt like he was looking deep into me. It was unnerving, but I didn't - couldn't - look away. It felt like a long time before his companion said something to him and he blinked (is it in my imagination of the moment, or did it really happen that he nodded?) and looked away. I realized at that point that I had been holding my breath, and blinked myself, then exhaled and stubbed out my cigarette and sat while he stood. Four other people joined him and together they walked into the lecture hall. All I could think was, "What was that?"

I staggered to my feet and shook my head, then followed the parade of people headed in. I took my seat next to George, and I don't remember what happened next. I do know Caponigro took the podium on stage and began speaking about his journey as a photographer, how he saw the art as an avenue to his own spirituality, how his training as a classical pianist had contributed to his photography - something he and Ansel had in common - and how if we wanted a pathway to self-discovery and a way of seeing that was uniquely our own - a seeing into ourselves and what this life could hold for us - then photography just might be the answer.

Remember the first paragraph of this post? The one sitting up there pregnant with all the lost possibility of a life lived to its fullest? My mother's life? An artist who never got to get there, to the point Caponigro was describing, the religion surrounding the desire to create that had the potential to save her from the life she ultimately ended up living? That paragraph can't begin to hold all the pain and sadness that suddenly washed over me with each new statement that Paul Caponigro made on stage that evening. A half-an-hour in, I was far more than exposed. I was turned inside out. Without a word to George, I stood up and walked out. I went to the restroom, and for ten minutes I wept. I wept for the child I used to be. But more, I wept for my mother, and all the dreams she left in all those empty bottles. And somewhere in those ten long minutes alone in a cold public restroom surrounded by the mountains of Yosemite, I grasped the thread of what has become my life. I left the belief that you can never live your art on that bathroom floor, wrapped up in tissue, and as sad as I was for my mother, I was equally as determined to never let that happen to me.

I composed myself eventually (so to speak), and walked back into the hall, but I didn't go back to my seat. I was aware enough of the epiphany that was being born inside me to know I was going to buy one of Paul Caponigro's prints that evening. I just didn't know which one. And all his prints were just inside the door on those tables, with no one else around. Everyone was listening to him as he continued speaking and I listened also as I walked around the tables, narrowing down my choice. It didn't take as long as you might think. Before he was done, I had it down to two prints:

The first was a drop-dead gorgeous photograph of a river moving away from the photographer. I had learned during the first part of the workshop that the material that makes black-and-white prints so rich is the silver in the gelatin. This photograph, taken in the woods in Redding, Connecticut is silver in all its glory. I fell in love with it immediately, and for me it outshone all the other prints on the table in a big way. I still feel that way about it.

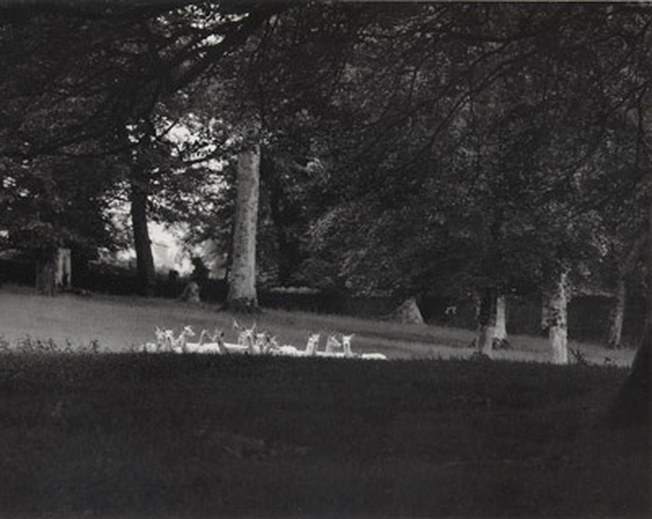

But there was this other photograph that just kept calling me. It was of a group of white deer standing just over a knoll the woods in Wicklow, Ireland, and it wouldn't let go. I moved the two prints gently together onto one of the tables. I knelt in front of them (I really did this) at the back of the hall and studied both of them for a long time. It was obvious why I liked the river print so much - it was beautiful. But what, I asked myself, was the attraction to this other one? As far as that went, there were several others on the table that were more... appealing as photographic prints. But why did this particular one keep speaking to me? As Caponigro finished his lecture and the applause started, it hit: this was a metaphor for us - for photographers. We are all made of the same stuff - the same needs, the same desires, curiosity - but we all look in different directions. We all see differently. And there it was. That print of those deer hangs now at the top of the staircase in my home, as it has since the day I brought it through the door.

But there was this other photograph that just kept calling me. It was of a group of white deer standing just over a knoll the woods in Wicklow, Ireland, and it wouldn't let go. I moved the two prints gently together onto one of the tables. I knelt in front of them (I really did this) at the back of the hall and studied both of them for a long time. It was obvious why I liked the river print so much - it was beautiful. But what, I asked myself, was the attraction to this other one? As far as that went, there were several others on the table that were more... appealing as photographic prints. But why did this particular one keep speaking to me? As Caponigro finished his lecture and the applause started, it hit: this was a metaphor for us - for photographers. We are all made of the same stuff - the same needs, the same desires, curiosity - but we all look in different directions. We all see differently. And there it was. That print of those deer hangs now at the top of the staircase in my home, as it has since the day I brought it through the door.

The story doesn't end there. I had one more surprise in store that evening. After I bought the print and made the arrangements to have it shipped to Alaska, I stood in line at the table where Caponigro was signing books, my copy of Landscape in hand. I watched him sign several other student's' books. He signed each one the standard way, asking who it was dedicated to, then writing his name inside the front cover. But when I handed him my book, he didn't ask me anything. Again he just stared into me for a long moment, opened the book to the following passage on page 67, and signed his name there:

"All that I have achieved are these dreams locked in silver. Through this work it was possible, if only for brief moments, to sense the thread which holds all things together. The world, the unity of force and movement, could be seen in nature - in a face, a stone, or a patch of sunlight. The subtle suggestions generated by configurations of cloud and stone, of shape and tone, made of the photograph a meeting place, from which to continue on an even more adventurous journey through a landscape of reflection, of introspection."

And, by the way, he signed his name with an exclamation point. I'm looking at that page right now, and the signature still sends a world of energy my way. Why? I have no idea. But I know I walked out of that lecture hall changed forever. I knew, somehow, and I hadn't a clue how yet, that I would commit to photography as a major force in my life.

Next time: The Rest of the Story.

"All that I have achieved are these dreams locked in silver. Through this work it was possible, if only for brief moments, to sense the thread which holds all things together. The world, the unity of force and movement, could be seen in nature - in a face, a stone, or a patch of sunlight. The subtle suggestions generated by configurations of cloud and stone, of shape and tone, made of the photograph a meeting place, from which to continue on an even more adventurous journey through a landscape of reflection, of introspection."

And, by the way, he signed his name with an exclamation point. I'm looking at that page right now, and the signature still sends a world of energy my way. Why? I have no idea. But I know I walked out of that lecture hall changed forever. I knew, somehow, and I hadn't a clue how yet, that I would commit to photography as a major force in my life.

Next time: The Rest of the Story.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed