Today is Earth Day 2013. If you do nothing else today, watch the video created by 350.org and released last night. Better yet, watch it, then join up. Do it for your future, your children's future, your grandchildren's future. If we don't change things, they may not have one.

|

The rest of the workshop is a blur, but highlights remain with me. We had our half-day session with Ansel in a small grove of Douglas fir trees not far from the lodge. Ansel was accompanied by his assistant Alan Ross, who carried the view camera and tripod. Ansel stopped and had Ross set the camera up twenty feet from three of the trees growing together. Ansel disappeared under the dark cloth and framed and focused the image while we waited. With a flourish he came out and offered the cloth to us. "Who wants to take a look?"

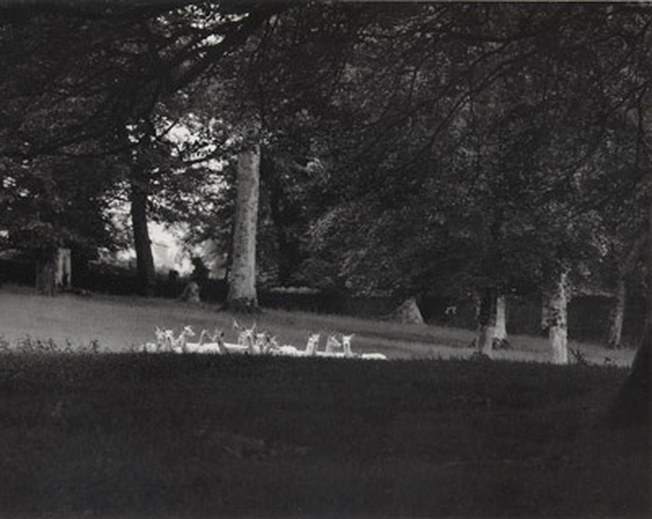

Who wants to look at an image Ansel Adams himself composed? Are you kidding me? We fell over ourselves getting behind that camera. It was upside-down and reversed left-to-right, but we all got the idea. Ansel waited patiently until we each had our turn, then asked us, "What do you think?" We all nodded and said we thought it was a good image to shoot. What else were we going to say? Ansel looked at us and said, "I would have taken that shot twenty years ago." He then instructed Ross to move the tripod half the distance to the trees, framed and focused again, and invited us to check out the new image. Where before we had the roots, the textured bark and even a few low-hanging branches, now the photograph was only about the base of the trees and their roots. We all agreed this was better. Again he nodded and looked at the trees. "That one I might have taken ten years ago." The third and final image he showed us was composed just a few feet from one of the trees. The photograph was all about the forms and textures of the bark, and the soft light wrapping around one side of the tree. That light had been there all along, but none of us had noticed it. "This is what I'll take today," Ansel said with a smile and a wag of his finger. "Remember, if it's not good enough, you're not close enough." I found out later that that quote is actually attributed to another giant of photography, photojournalist Henri Cartier-Bresson, but Ansel said it first for me, and it stuck. As if it mattered, we were all in agreement. This was the best of the three photos Ansel composed that day by far. I also got to sit with George as he and I had coffee and tea with Paul Caponigro on the last day of the workshop. George was searching as hard as I was in those days, and he wanted to know how he could know what path he should pursue. Like Ansel and Caponigro, George was a pianist, and loved both the piano and photography. Caponigro was patient with the two of us, and more or less reminded us that it was up to us to decide how and what we were going to do with our lives. He wished us luck, and told us to trust ourselves. Oddly enough, I still carry a scrap of paper in my wallet with my mother's handwriting on it, and it says the same thing: "Know thyself. Love thyself. Trust thyself." I don't know if George ever found his answer. We said our goodbyes, and joined up with Jim and Ray for our last afternoon and evening together before we all headed home. We were giddy with the emotions the entire week had inspired, and took a bus ride on an open-topped double-decker tour bus around the park. As we rode, we laughed, told stories, and generally let off steam. I remember shooting some photos with my teeth, telling the group that this was "The Jimi Hendrix Method" of photography. At some point Ray stopped and looked very serious and said, "You know what I'm trying to communicate when I photograph - whether it's a photo of a flower, a landscape or a person?" We all shook our heads. "It's, 'Well, GOLLL-EEE, wouldcha look at THAT?!?" After all the high-minded talk about photography during the week, it struck us all as hilarious. I know. You really had to be there. I stayed in touch with Ray for the next 10 years or so until his sister wrote me that he had passed away sometime in the early nineties. We had several long and very good phone conversations about photography and the world of fine-art photographers, and I find that I miss him more than ever when I think about that time. George and Jim and I exchanged Christmas cards for a few years, but lost touch after that. The internet tells me George is still out there, and I actually just tried calling him, but got an automated answer machine. I'll keep trying. I'd like him to read this, and tell me whether or not I got it right. The Jim Mulvaney that answered my call yesterday wasn't the one I knew. I'll keep looking. And after writing this, I'm developing an urge to dust off the 4x5 view camera and take a trip to the Cascades for old times' sake. I'll think about Goerge, Ray and Jim. I know I'll think about mom. She loved the spring. But more than anything, I'll think about Ansel, Roy DeCarava, Marion Patterson and Paul Caponigro and the week that they changed my life. I'm grateful they did. What about you? Do you have heroes in the photo world? I'd love to hear your stories. Leave a comment or two when you get a chance. And thanks for stopping in. My mother was an artist. Both my brothers attribute at least some of their artistic talent to her, and I know my desire to write and to become a photographer was often encouraged by her - if not in words, in her actions. Yet I experienced a very different woman as I grew up than my brothers and sister knew. By the time I was in early adolescence, the artist had taken a serious backseat to the alcoholic, and though I saw glimmers of her talent with a pen and pencil, it was only the briefest of glimpses. In my own quest to find some art form or way of expressing myself, I grew up with a very potent unspoken message - that it is impossible to find one's path through art. I carried that belief with me up to the day I heard Paul Caponigro speak to the 1979 Ansel Adams Workshop attendees, other instructors and even Ansel himself. George and I arrived early and put our jackets on chairs front and center, then browsed the matted fine-art portfolio prints Caponigro had put out on display, covering two eight-foot tables entirely. All black-and-white, they were soft and delicate images of his travels, images I have still, enclosed in the pages of his coffee-table book Megaliths. I stopped at the table that held his books, and bought the one I felt I could afford at the time, Landscape, intending on getting him to sign it at the end of the lecture. I took it with me as I went out the front entrance to have a cigarette 15 minutes before he was to speak. The entryway I found myself in had low stone walls on either side of the sidewalk, and as I sat on one side and lit up, I noticed I was directly opposite Caponigro and another man, presumably either a student or assistant to one of the other instructors. They were engaged in a quiet but obviously intense conversation, speaking in low tones. For a few minutes I kept what I thought was a clandestine eye on them while browsing the book I had just purchased. Then they both seemed to relax and disengage from their conversation. The other person said something to a student walking by, and I looked up just as Caponigro turned and looked directly at me. We stared at each other for what seemed an abnormally long time. You know those rare moments in time when you and another person connect on a level that surprises you? This was that, times ten...or maybe twenty-five. I don't know how to quantify it, but I know that at that moment I was a bit exposed emotionally - raw even, from the other events of that day, and when we locked gazes I felt like he was looking deep into me. It was unnerving, but I didn't - couldn't - look away. It felt like a long time before his companion said something to him and he blinked (is it in my imagination of the moment, or did it really happen that he nodded?) and looked away. I realized at that point that I had been holding my breath, and blinked myself, then exhaled and stubbed out my cigarette and sat while he stood. Four other people joined him and together they walked into the lecture hall. All I could think was, "What was that?" I staggered to my feet and shook my head, then followed the parade of people headed in. I took my seat next to George, and I don't remember what happened next. I do know Caponigro took the podium on stage and began speaking about his journey as a photographer, how he saw the art as an avenue to his own spirituality, how his training as a classical pianist had contributed to his photography - something he and Ansel had in common - and how if we wanted a pathway to self-discovery and a way of seeing that was uniquely our own - a seeing into ourselves and what this life could hold for us - then photography just might be the answer. Remember the first paragraph of this post? The one sitting up there pregnant with all the lost possibility of a life lived to its fullest? My mother's life? An artist who never got to get there, to the point Caponigro was describing, the religion surrounding the desire to create that had the potential to save her from the life she ultimately ended up living? That paragraph can't begin to hold all the pain and sadness that suddenly washed over me with each new statement that Paul Caponigro made on stage that evening. A half-an-hour in, I was far more than exposed. I was turned inside out. Without a word to George, I stood up and walked out. I went to the restroom, and for ten minutes I wept. I wept for the child I used to be. But more, I wept for my mother, and all the dreams she left in all those empty bottles. And somewhere in those ten long minutes alone in a cold public restroom surrounded by the mountains of Yosemite, I grasped the thread of what has become my life. I left the belief that you can never live your art on that bathroom floor, wrapped up in tissue, and as sad as I was for my mother, I was equally as determined to never let that happen to me. I composed myself eventually (so to speak), and walked back into the hall, but I didn't go back to my seat. I was aware enough of the epiphany that was being born inside me to know I was going to buy one of Paul Caponigro's prints that evening. I just didn't know which one. And all his prints were just inside the door on those tables, with no one else around. Everyone was listening to him as he continued speaking and I listened also as I walked around the tables, narrowing down my choice. It didn't take as long as you might think. Before he was done, I had it down to two prints: The first was a drop-dead gorgeous photograph of a river moving away from the photographer. I had learned during the first part of the workshop that the material that makes black-and-white prints so rich is the silver in the gelatin. This photograph, taken in the woods in Redding, Connecticut is silver in all its glory. I fell in love with it immediately, and for me it outshone all the other prints on the table in a big way. I still feel that way about it. But there was this other photograph that just kept calling me. It was of a group of white deer standing just over a knoll the woods in Wicklow, Ireland, and it wouldn't let go. I moved the two prints gently together onto one of the tables. I knelt in front of them (I really did this) at the back of the hall and studied both of them for a long time. It was obvious why I liked the river print so much - it was beautiful. But what, I asked myself, was the attraction to this other one? As far as that went, there were several others on the table that were more... appealing as photographic prints. But why did this particular one keep speaking to me? As Caponigro finished his lecture and the applause started, it hit: this was a metaphor for us - for photographers. We are all made of the same stuff - the same needs, the same desires, curiosity - but we all look in different directions. We all see differently. And there it was. That print of those deer hangs now at the top of the staircase in my home, as it has since the day I brought it through the door. The story doesn't end there. I had one more surprise in store that evening. After I bought the print and made the arrangements to have it shipped to Alaska, I stood in line at the table where Caponigro was signing books, my copy of Landscape in hand. I watched him sign several other student's' books. He signed each one the standard way, asking who it was dedicated to, then writing his name inside the front cover. But when I handed him my book, he didn't ask me anything. Again he just stared into me for a long moment, opened the book to the following passage on page 67, and signed his name there: "All that I have achieved are these dreams locked in silver. Through this work it was possible, if only for brief moments, to sense the thread which holds all things together. The world, the unity of force and movement, could be seen in nature - in a face, a stone, or a patch of sunlight. The subtle suggestions generated by configurations of cloud and stone, of shape and tone, made of the photograph a meeting place, from which to continue on an even more adventurous journey through a landscape of reflection, of introspection." And, by the way, he signed his name with an exclamation point. I'm looking at that page right now, and the signature still sends a world of energy my way. Why? I have no idea. But I know I walked out of that lecture hall changed forever. I knew, somehow, and I hadn't a clue how yet, that I would commit to photography as a major force in my life. Next time: The Rest of the Story. I woke up the morning of the fourth day of the workshop on the floor of George's room. I vaguely remember him offering me a "floor to sleep on, if you want it," for the rest of the workshop, and I gratefully accepted. The room had heat and walls, and was located much closer to our meeting halls. As long as George could stand it, the floor was a luxury to me.

Feeling pretty ragged from the beer and tequila the night before, I nursed a quick breakfast and headed for my morning session with Marion Patterson. I had never heard of her before, but she had worked extensively in color slide film, and to my amazement, she photographed many of the subjects I loved and photographed myself: closeups of flowers and leaves, landscapes, sunsets, sunrises, reflections in water, clouds. She showed us a slide show with two projectors, synced to classical music, something I had been wanting to do with my own work. I was stunned...and a little overwhelmed. The first three days for me was spent learning things that were new and mostly foreign to me, like the Zone System, which required a large format camera (in those days) and all its accessories, a myriad of tests of papers, films and developers, a hand-held light meter, a densitometer and a knowledge of archival printing and matting...none of which I had, had access to, or really understood. I felt like I was being educated on how much I didn't know...and in reality, I was. But suddenly here was Marion Patterson showing her work and in effect, saying to me, "What you're doing, and what you know now, can be enough." I found myself reeling from the validation and empowerment her work and words brought me. I recall walking out of her workshop thinking that I might actually find this art form within my reach, if I chose to grasp it. A side note here, for Marion Patterson taught me something I have never forgotten, and still use to this day - I did it just this week photographing daffodils growing inside pampas grass: she said that when she photographs her subject (or her subject picks her), after the exchange - the exploring and discovery that the experience of engaging the subject brings, whether it's a rock, a flower or an animal in front of the lens, she stops and thanks the subject for the sharing. That struck a chord with me. It may sound all "woo-woo" to you, but consider what you take away from such an experience - a learning, a growing, a new way of seeing...a seeing not only of the subject, but of those pathways inside your own mind, heart and vision that, had you not engaged that subject, you would never have discovered. Is that not worthy of the respect and the honor a simple 'thank you' transmits? I have always thought so. My afternoon session was with Roy DeCarava, who actually looked through the pathetic portfolio I brought with me - cheap, drugstore prints on multicolored, cheaper craft-store mats. And without either of us knowing it at the time, he taught me how I was going to teach photography to my students for decades to come: he complimented me on my images, the vision I had, what I was trying to accomplish. Then he suggested how I could make it more effective. He tried to understand what it was I was trying to do, and from inside that context showed me how to do it better in a variety of ways - composition, matting, focus, depth-of-field. I walked away educated, but mostly, I felt respected and acknowledged. And that was huge, and left me wanting more. I just now looked at my notes from his session, and the last thing I wrote was, "What is your motivation? What are you trying to say?" Indeed. Whew. What a switch from the previous three days of technical input. Just as I was saying, "My brain is fried," the coin flipped to be more about why we photograph rather than how we photograph. But I wasn't done with the journey yet. This, as potent as it was, was just the setup. The punch that landed hardest was thrown by fine-art photographer Paul Caponigro at that night's evening lecture. Caponigro was unknown to me before the workshop. My new roommate George, however, was very familiar with his work and his reputation. George told me Caponigro was a master at fine art black-and-white, large format works, on par with Ansel in terms of his stature in the field. Caponigro also photographed nature, but was drawn to places and subjects that held spiritual power, such as Stonehenge and the stone circles of Ireland. He was known to be extremely intense, occasionally reclusive, and had been fighting a spell of ill health. Some of his half-day sessions at the workshop had been canceled because he was not feeling well, but George was determined to seek an audience with him if it was at all possible before the week was done, and I was welcome to come along. Needless to say, I was once again a bit intimidated by another daunting figure, but I had no idea what was about to happen as George and I finished dinner and headed to the lecture hall early so we could get good seats. Next time: A Lecture for a Lifetime. Stay tuned. I must say, when it comes to workshops, and I have attended a lot of them over the years, I started big. Ansel died five short years later, but in 1979, just recovering from his first heart attack, he was back teaching at Yosemite like he had for decades. I was 29, a Special Education teacher living in Alaska, and I really had no clue about what good photography was. I was just enthusiastic and interested. And nervous. Was I up to this?

My bus arrived in the late afternoon, and I soon discovered that the camping area was a good mile from anything else. I set up my tent in the dimming evening summer light, listening to the Merced river running by and watching the shadows work their way up the granite cliffs in the distance. It was the first week of June, and I came to the quick realization that even though class hadn't started yet, I had already made a terrible mistake: thinking I could save some money, I intended on camping for the week. The problem was that the campground was a good fifteen-minute hike (minimum) from everywhere else I needed to be during the workshop. This meant getting up an hour earlier than everyone else, and it also meant hiking a mile at the beginning of the day, and then again at the end, in the dark, lugging my camera bag and tripod with me both ways. Not the best plan. Plus, even in those days bears were an issue in the park. I had a very restless first night. Still, day one came, and I hiked to my first session, feeling a bit sheepish that I was the only workshop atendee, as far as I could tell, that had no transportation and no room to stay in. By the time I got to the lecture hall, I was wringing wet with sweat. Did I forget to mention that the hike was all uphill from the campground? I put my gear in a corner where everyone else had dropped theirs, and sat in a folding chair, hoping Ansel was going to speak. Instead we got a workshop staffer, probably someone important and famous today, but I can't for the life of me remember who it was. He told us we were going to be divided into groups of twelve, and our small groups would rotate to different instructors throughout the week. Each day we'd have two sessions: one in the morning, one after lunch, with a keynote address each evening. We'd get a half-day with Ansel, plus his lecture. But we'd also get half-days with photo-legends I wasn't yet familiar with: Roy DeCarava, a street photographer from Harlem; Jim Alinder, a photo-historian; Al Weber, a photographer proficient in color printing; Alan Ross, Ansel's assistant; and Marion Patterson...I'll get to her later. The first day of class I met and made three friends: Jim Mulvaney from Virginia, Ray Tocco from L.A., and George Akerley, a professional pianist from Oaklyn, New Jersey. Over the course of the week we became inseparable. We somehow connected in that crazy, electric and heady atmosphere, and all we knew was when we'd finished with our class sessions, our heads were full and we all needed to debrief with people who understood what we were going through. We'd head to the lodge for beers and pizza, staying late each night, talking, telling stories, rehashing lectures, soaking it up. Only after we'd emptied our heads of all we'd heard and seen did we finally collapse and head to bed. It was a long walk in the dark back to the tent. So that this post stays relatively short, let's divide the workshop in half: the first half of the sessions were head-based for me. It wasn't by design; it just worked out that way. I learned about color printing, the Zone System, large-format photography, f-stops and shutter speeds, ways of "Pre-Visualizing," testing materials, developers, paper, films. It took a few days, but I remember complaining to my new buddies that my head was getting so full I thought it would explode. We were all relatively young, and Jim, George and Ray had more knowledge of the fine-art world of photography than I did. I learned as much from the three of them as I did from my instructors. It was an immersion experience in photography, photo-history, photo-process and technique, and I was getting saturated. We stayed up late that third night, and I got a little too drunk. It was while I nursed a hangover the next day that everything changed. More on that next time. Like I said, let me know if you like this stuff... Back in the day, I was a high-school yearbook photographer. The school I attended back in Indiana only had two photographers for the annual...a junior and a senior. I was appointed the junior photographer, and held that position for the better part of the year, until one day I decided to skip school with some friends (the ONLY time I ever skipped, by the way - and that's the unfortunate truth), and in the infinite wisdom of my 16-year-old-self, we drove past the school during lunch. Crossing the street as we went by was the yearbook teacher, Mr. VanAllen. He looked right in the rear window at me. The next day, I was off the staff, banished for "conduct unbecoming." I never talked to him again.

It wasn't until I had finished college at Indiana University six years later that I picked up a camera again. I bought a Canon AE-1, a Vivitar 70-200mm macro lens and The Amateur Photographer's Handbook to take on my first trip to Alaska in the summer of 1974. I read the book from cover-to-cover, and shot Kodachrome slides all the way up and down the Alaska Highway, of mountains, sheep, moose, autumn colors, goats, rivers, the ocean. A few of those shots were actually good, and after landing a teaching job to Kenai in 1975, I decided to try to sell a few at the local arts and craft fair held after Thanksgiving in the mall. I was sitting in the booth on the main floor of the mall, and every few minutes a flash would fire inside the store just behind me. When I took a break later that afternoon, I wandered in and met Roy Mullin, the owner of a new photo studio in town, Visual Sensitivity Unlimited. It wasn't long before we were the best of friends, taking pictures out in the woods together, telling stories, making new ones together to tell, and generally having fun with each other. We were the same age, loved the Beatles and rock & roll, though, apologies to Roy, I could never get into Frank Zappa like he did. But we certainly could have fun, and when we worked out a deal where he trained me in black-and-white darkroom work, I was in heaven. A very dust-spot-ridden heaven much to Roy's dismay, but heaven to me. This was in ancient B.I. America...Before Internet. When Roy suggested we write away for applications to the Ansel Adams workshop in Yosemite for the summer of 1979, I jumped at the chance. I was still shooting mostly color slide film, but was intensely interested in fine art black-and-white. I used to drive Roy crazy by shooting four or five rolls of film on a trip with him, but waiting two or three or sometimes six months before sending it off to be developed. He got his revenge on me when I sent in my application to the workshop and he didn't. And I got accepted. June of 1979 found my wife Veronica and I in the Weston Gallery in Carmel, California a week before the workshop, looking at galley proofs of Ansel's newest book, Yosemite and the Range of Light, straight from the publisher. They were holding it for Ansel to come approve the photographs printed within. As we stood pouring over the proofs (the curator let us look at them once he heard I was attending the workshop), we were speechless at the richness and beauty of the images on the pages - until we would see one that was hanging as a silver print that Ansel himself had printed, on the wall behind us. When we would turn and look - comparing the ink on paper to the actual print, we were floored. Beside the print, the images we had seconds ago thought were so fantastic faded into just pale representations of the reality. If you have never seen an Ansel Adams print in real life and you are interested in photography at all, get yourself to a gallery or attend an exhibition of his work. It is monumental. I have never felt - before or since - that I could literally walk into a black-and-white landscape like I did gazing at those marvelous prints. I could sense the air in the scene, and felt like if I had a mind to, I could just go for a stroll within the image. Needless to say, I was transported. And also a little bit intimidated. What was I, an imposter posing as a photographer, thinking? After a long talk, Veronica reminded me that I wasn't expected to be proficient - I was a student, and I was going there to learn. And learn I did. A week later I was surrounded by not one, but several masters of the craft. 60 students arrived not knowing what to expect. I don't know how many of us were transformed by the week we spent there, but I know I was. I came home changed. More on what happened at the workshop that stirred me up and remade me next time. Thanks for stopping by, and if you like this stuff, please let me know. Writing a blog is sometimes like yelling into the wind. You never really know if you are heard. |

about patrickphotography is a state of mind. archives

April 2014

categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed